Making of a Painting IV: Nicholas Black Elk (2 of 2)

Introduction

The previous post provides the historical, theological, and literary background to our depiction of Nicholas Black Elk. In what follows, I turn to the painting itself and explain how we integrated that information into a compelling and at times ambiguous portrayal that honors both the power and the complexity of Black Elk’s story.

Previous Depictions

As always, we began this commission by reviewing previous depictions of Black Elk in order to place our own portrayal in the context of traditional iconography. Since his cause for canonization was initiated in 2017, a number of hagiographic paintings have been created by Christian artists. The best known include contemporary Eastern-style icons by Andre Prevost (below) and Br. Robert Lentz, OFM, along with a powerful portrait by Fr. John Giuliani.

Nicholas Black Elk (2022), by iconographer Andre Prevost. Used with permission.

All three of these depict Black Elk wearing the buckskin shirt seen in a famous photograph taken by Joseph Brown, and two show the holy man holding both a rosary and a pipe (echoing his grandson’s statement quoted in the previous post).

We adopted this emerging convention regarding Black Elk’s attire and symbolic accoutrements but made the halo implicit in the compositional arrangement rather than explicit, since he has not yet been canonized.

Compositional Geometry

In addition to providing a tacit mark of holiness, the strong circular element of the compositional geometry of our painting echoes the “sacred hoop” that figures prominently in Black Elk’s religious thought.

This motif represents one of the many fundamental ways in which the Lakota worldview differs from its modern Western counterpart, with its highly linear conception of space/time.

The chiasm within the circle, meanwhile, evokes the Lakota symbol for the cardinal directions (as seen, for example, in this drawing of Black Elk’s Great Vision by his friend Stephen Standing Bear). Perhaps influenced by his Christianity, Black Elk also thought of the cross as the sacred meeting point between the path of life and the path of suffering, a metaphor that was at the heart of his spirituality.

Finally, the unabashed centrality of the composition, an approach sometimes termed “monolithic,” conveys an impression of mythic permanence. The geometric equilibrium is countered, however, by the inverted pyramid at the base of the painting. This unstable structure introduces an unsettled element—a lack of resolution that reflects the incomplete fulfillment of Black Elk’s vision, his lifelong struggle to understand its meaning, and the tensions arising from his efforts to live as both a Lakota and a Catholic.

Black Elk

My comments in a previous post about the pitfalls to beware when creating recognizable portraits of historical figures certainly applied to our depiction of Black Elk. In order to avoid being overly dependent on the angle, lighting, or expression of any one source image, we worked hard to reconstruct the three-dimensional form of his face from the many photographs taken during his lifetime.

We elected to depict Black Elk as an elder rather than a young man (à la Daniel Mitsui), most importantly because he is the sixth Grandfather of his vision (see below) but also to reflect his reputation for wisdom. At the age depicted, Black Elk would have been nearly blind, and in our painting the groping of his sightless eyes contrasts with the brilliance and clarity of the spiritual vision displayed around him.

We based our portrayal of Black Elk’s hairstyle on this 1948 photograph, where (in addition to the now-familiar hide shirt) he wears his hair somewhat longer than in most twentieth-century portraits (judging from other photos taken around the same time, it may in fact be a wig). Parted down the middle, the queues are wrapped in strips of otter fur and tied with buckskin thongs and beaded fasteners decorated with ermine tails (as also seen in Bill Groethe’s famous portrait taken at the Little Bighorn reunion that same year).

The design of Black Elk’s pipe is based on a specimen believed to have belonged to him and on photographs by John Neihardt and Brown. The bowl is carved from Catlinite and features a lightning-motif inlay made of lead from melted bullets. The ash stem is decorated with quillwork, silk ribbons, and the tailfeathers of an immature golden eagle.

The Vision

Approach

The visual panorama of Black Elk’s mystical experiences is wide-ranging and has been described as encompassing the totality of Lakota cosmology. We could only hope to scratch the surface of its expansive imagery and rich symbolic content in our painting and had to be selective in our sampling from a tremendous amount of material. In the end, we elected to focus this sampling on elements that have parallels in the Judeo-Christian Biblical tradition.

These parallels abound, and some authors have made much of them. I feel it is important to note, however, that there is little evidence in the documentary record that Black Elk himself attributed special significance to them, much less that he subjected his memory of the visions to a wholesale restructuring following his baptism. Some points of correspondence between the Great Vision and pre-existing Christian imagery are of the sort that one might expect from sheer coincidence, and the rest may be explicable on the basis of common archetypes. (The vision of the “Red Christ” in the Ghost Dance trance, of course, is a different matter—here there is a direct relationship, reflecting the influence of Christian theology on the cult’s teachings.) Regardless of their cause, we decided to focus on these parallels as a visually evocative means of honoring Black Elk’s dual allegiance to Christian doctrine and Lakota cosmology.

In addition to being selective in our sampling of scenes and motifs, we also had to simplify the elements we sampled. As in Biblical apocalyptic literature, the fantastic imagery of the Great Vision does not always lend itself to literal illustration. For this reason, there is a long history in the Christian artistic tradition of reducing the complexity of such imagery to make it visually intelligible.

For example, the Lamb of the Apocalypse is a popular subject of Christian liturgical art, but rarely does one see the sheep in question depicted with seven eyes and seven horns, as described in the text (Rev 5:6).

Simplified renditions of the Lamb of Revelation, as in Jan van Eyck's iconic Ghent Altarpiece (left), have stood the test of time better than more literal views, as in the Dyson Perrins Apocalypse (right).

Similarly, in Ezekiel’s vision (Ezk 1), God is enthroned upon four cherubim in the form of a lion, an ox, an eagle, and a man. As the description unfolds, the creatures become increasingly difficult to imagine, as we learn that they have numerous faces, wings, and even wheels covered with eyes. Raphael’s striking depiction of the scene abstracts from these problematic complexities and in so doing manages to capture the essence of the vision better than if he had committed himself to the entirety of the textual details.

Compare the visual impact of Raphael's ca. 1518 Vision of Ezekiel (left) with the more literal interpretation on the right (anonymous, ca. 1500)

The same process was operative in our approach to the descriptions of Black Elk’s visions.

Content

Black Elk’s original account of the Great Vision was related to Neihardt over the course of several days of intensive interviews. What follows, therefore, is by necessity a highly abridged summary of some of the key features that are relevant to our painting.

In his dream, Black Elk was taken to a celestial dwelling beneath a flaming rainbow, where he met six Grandfathers. Four represented the sacred cardinal directions, and another was Wakan Tanka (often translated “Great Spirit” or “Ultimate Mystery”), who later turned into an immature golden eagle. The sixth turned out to be Black Elk himself as an old man.

As the dream progressed, the Grandfathers conferred on the boy a series of gifts that represented the power to help his people thrive. For example, the Grandfather of the North provided a medicinal herb (representing healing), the one from the East a sacred pipe (representing peace), the one from the South a sprouting stick (representing flourishing life), and the one from the West a bow and arrows (representing defense against enemies). Black Elk took the gifts and proceeded to battle various monsters, which stood for drought and other threats to human welfare.

At one point, the boy was also offered a gift by a Spirit of War, who took the form of an evil-looking horned figure surrounded by flames. Amid the smoke, four fierce warriors galloped, each on a horse of a different color. Two wore horned headdresses (one of which was the full head of a living bison), while the other two wore eagles in their hair. One of these latter horsemen also bore a lance in the form of a serpent.

The flaming figure offered Black Elk a “soldier weed” that could make him a deadly warrior like these horsemen. Black Elk ultimately decided not to use this herb, even though it would have granted him tremendous prestige. Instead, he began to see that his commission from the Grandfathers was to promote the well-being of the entire world and not just the tribal dominance of his own people.

Eventually, Black Elk returned to the celestial lodge of the Grandfathers and, imbued with a powerful new sense of purpose, was escorted by heavenly messengers back to his earthly body.

Depiction

We set our version of Black Elk’s vision against a starry, nebula-like backdrop in order to evoke its cosmic significance. The five Grandfathers (Black Elk himself, now an old man looking back on the experience, is the sixth) are seated beneath a fiery rainbow (cf. Ezk 1:28, Rev 4:3), and those representing the cardinal directions present their gifts for Black Elk.

The pipe held by the East is similar to the one described above, while the design of the West’s quiver is based on several surviving Lakota specimens from the second half of the 1800s. The sprouting stick in the hands of the South appears as a sprig of cottonwood (which Black Elk identified as the species) and evokes the Biblical Tree of Life (Gen 2:9, Rev 22:2) in its form and symbolic meaning.

The four elders are wrapped in bison robes and wear old-time clothing of animal skin typical of the mid-nineteenth century.

This schematic shows how the loose-fitting shirt worn by Plains Indian men was constructed from two deer hides.

While the archetypical cut of the traditional Plains shirt featured a triangle-shaped bib at the neck (mimicking the loose flap of the animals’ skin that would hang down on the chest/back in the earliest examples), several old photographs and archival specimens of Lakota shirts from ca. 1870 show a rectangular bib.

Two Oglala chiefs in this 1870 photograph wear war shirts with rectangular bibs.

Oglala chief Slow Bull wears a Crow-style shirt with rectangular bib in this 1872 portrait.

Several of the Grandfathers in our painting have neck flaps of red trade cloth in this format.

Shirts worn by Plains tribal leaders frequently had elaborate fringe made from locks of human hair wrapped in porcupine quills. Such articles are often called “scalp shirts” because of the decoration’s presumed origin in trophies taken from slain enemies, but among the Lakota these fringes were sometimes made from hair donated by kin and represented responsibility to the in-group rather than demise of the out-group.

The shirt worn by the fifth Grandfather, Wakan Tanka, is based closely on surviving specimens of Oglala leadership shirts from the 1870s, including the so-called “Red Cloud shirt.” It features decorative strips with seven tracks of lazy-stitch beadwork on the sleeves/shoulders and painted designs representing celestial power. Wakan Tanka also wears leggings of scarlet wool with wide side flaps, hoop earrings, and bilateral braids wrapped in strips of indigo saved-list cloth, all very fashionable among central Plains men in the 1860s and 1870s.

The Lakota concept of Wakan Tanka, while differing in important respects from anything in Western cosmology, is the closest analog in the Siouan tradition to the Christian idea of the Creator God. Not only is Wakan Tanka the deepest and most sacred mystery, transcending human knowledge and intimately connected with the origins of the universe, but this mystery can be thought of as a unity and as a multiplicity of benevolent forces at once. Indeed, from the time that the Bible was first translated into the Dakota language in 1880, “Wakan Tanka” has been used as the Siouan term for the Judeo-Christian Godhead. Black Elk himself used the phrase in this sense in letters he wrote as a catechist, as do Lakota-speaking Christians today.

To make this connection explicit, we gave the fifth Grandfather a triangular halo, which in the Western symbolic tradition denotes God the Father/Creator.

Holy Trinity, by Francesco de Mura (ca. 1741)

In Black Elk’s vision, a golden eagle proceeds from the figure of Wakan Tanka. In modern-day Lakota Christian iconography, the eagle is used in place of the dove as a symbol of the Holy Spirit (who, in both Catholic and Orthodox theology, is said to “proceed” from God the Father).

We depicted the eagle in perfect bilateral symmetry, matching that of the fifth Grandfather, in order to impart a higher degree of idealized perfection and thereby set these symbols of the Divine apart from the rest of the sacred figures.

The Trinitarian imagery is rounded out by a symbol borrowed from Black Elk’s Ghost Dance vision. In this 1890 trance, he saw a great blooming tree (cf. the Biblical Tree of Life in its guise as the life-giving Cross), in front of which stood a brilliantly shimmering man of ambiguous ethnicity with long hair, outstretched arms, and wounds in his palms.

Not surprisingly, those who promote Black Elk’s cause for canonization place a great deal of emphasis on this vision (“That is the Resurrected Jesus!” breathes his Jesuit biographer). This is not necessarily unfair, but it is important to understand the sociocultural context, in which many Lakota Ghost Dancers believed the Paiute prophet Jack Wilson to be a reincarnation of the Son of God. Black Elk himself downplayed the significance of the experience, and there is no evidence that he drew a connection between it and his subsequent conversion to Catholicism. Nevertheless, the vision’s overt Christological evocations add an important thread to the tapestry of his religious imagination.

Our depiction of the messianic figure highlights these associations by the symmetry of form (connecting him with the other Trinitarian symbols), side wound, cruciform halo, and universalized appearance (echoing Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian ideal).

Leonardo da Vinci, Vitruvian Man (ca. 1490, detail)

Returning to the Great Vision in the lower register, we depicted the fiery demon’s fierce warriors, who are reminiscent of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (Rev 6:1-8).

Our depiction of the destructive riders of Black Elk's vision (left) may remind viewers of the Biblical tradition's Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (right).

To use Christian parlance, the warriors represent the temptation to worldly power and glory that Black Elk considered but ultimately rejected. In one his few explicit references to Christianity in the Neihardt transcripts, Black Elk even connected his renunciation of the path of violence embodied by the soldier weed to his decision to convert to Catholicism. For this reason, the sequence involving the horsemen is among the most important keys to understanding Black Elk’s interpretation of the Great Vision, even though Neihardt chose to cut the whole scene from his final book. Our portrait returns this imagery to its rightful place as a central theme of the mystical cycle.

In our rendition, the equestrian figures are characterized by an infernal ferocity and possess a few fantastic accoutrements, such as the serpent-lance and the snorting bison-head hat. Otherwise, however, they appear as typical Lakota warriors of ca. 1870.

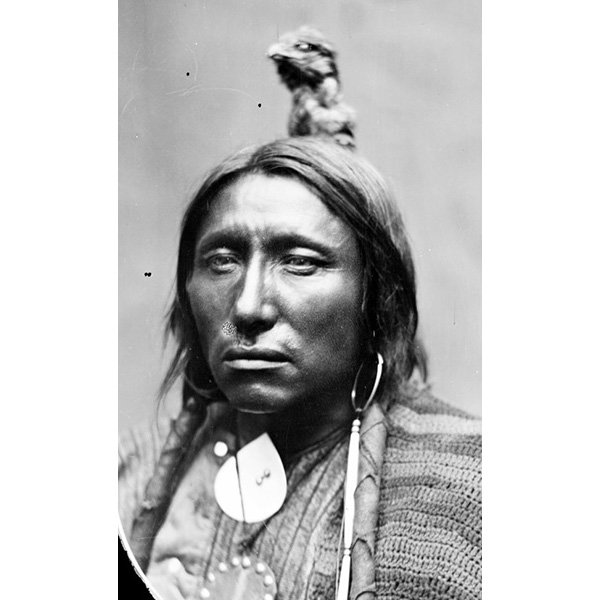

The feathered lance is modeled on a mid-century Lakota specimen, while the raptors worn in the hair are based on early photographs of Plains Indians with stuffed eagles on their heads, such as the following.

Long Otter (Crow), ca. 1905

Spotted Eagle (Lakota), 1880

Conclusion

At the outset of the last post, I explained that the commission to depict Black Elk was among the most humbling experiences of my professional career. Despite all the challenges, however, it has also been among the most rewarding. Black Elk was a complex and fascinating figure, and it has been a privilege to learn more about him during the course of this project and to help others discover his story through our artistic interpretation. As his canonization process unfolds, I hope that it offers encouragement to the many Catholics of Native descent who look to Black Elk as a model of Christian holiness lived out in an authentically Indigenous context.