Making of a Painting III: Louis and Zélie

Zélie Martin, ca. 1875

Louis Martin, ca. 1863

Introduction

When Goretti Fine Art received a commission to create an oil painting of Louis and Zélie Martin, it meant that we would face the perennial challenge of depicting saints who lived in the age of photography.

Patrons and the general public naturally expect such depictions to reflect the subjects’ actual appearance as recorded in the photographs. I was keenly aware, however, that as sacred artists we would have to be careful not to be too literal in our use of photographic reference material.

The acclaimed religious artist Anthony Visco has put it this way: “When our saints are represented only as they appeared in life, or as in their final photos, then we are recapturing only a momentary physical appearance—their image in time—and excluding their invisible likeness to God outside of time and into eternity. Although the photo may be inspirational, it remains in essence non-devotional.”

It was with this admonition in mind that I began the process of assembling the visual reference material we would need for our commission.

The Source Material

Louis and Azélie-Marie (“Zélie”) Martin, the pious parents of St. Thérèse of Lisieux and Servant of God Léonie Martin, are known from several photographs. As their popularity grew in association with the canonization process, numerous cut-and-paste composites, varying in technical sophistication, were created, seeming to show the spouses seated side-by-side (see, for example, here and here). Contrary to common belief, however, Louis and Zélie were never photographed together.

As I pursued my research, I learned that Zélie was photographed three times. In 1857, when she was 25 years old, she appeared with her younger brother Isadore (center) and older sister Marie-Louise (right):

This was shortly before she met and married Louis in 1858.

Now ten years into her marriage and 36 years old, Zélie sat for the following portrait:

After it was taken, a separate image of a son who died in infancy was cut out and glued on (in a primitive precursor of what we would call “Photoshopping”), as if he were being cradled by his mother.

The final photograph of Zélie, taken a year or two before her 1877 death of breast cancer, shows a respectable middle-aged matron:

The contours of her face have hardened and matured since her mid-twenties, but the tight bun that was her trademark remains little changed.

Meanwhile, the earliest extant photograph of Louis is from about five years after his marriage, when he was in his late thirties or early forties:

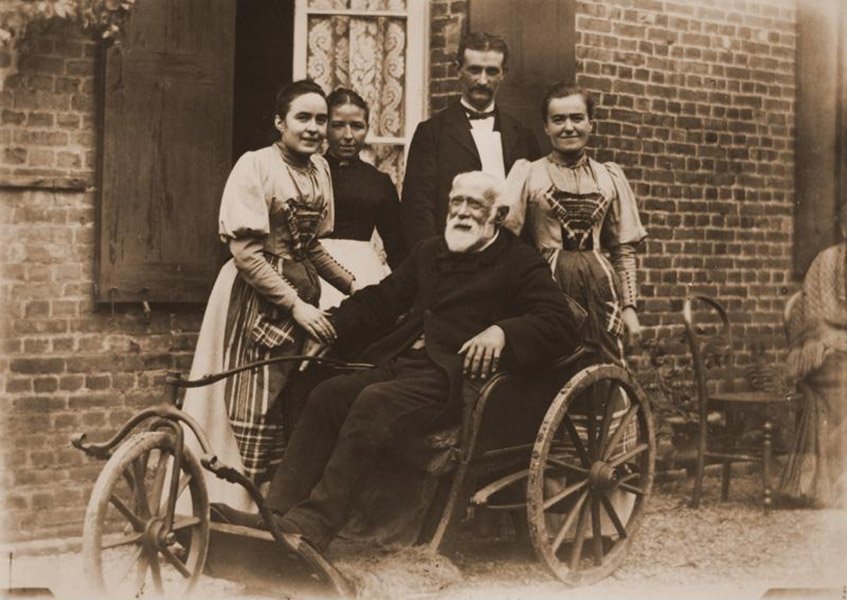

Other photographs of Louis are from significantly later: ca. 1881…

….1892…

…and at his death in 1894.

Not surprisingly, previous depictions of Louis and Zélie have been highly dependent upon these primary visual sources, with much devotional artwork (see, for example, here and here) consisting of little more than colorized composites of the nineteenth-century photos. These paintings highlight the pitfalls, alluded to at the beginning, of depicting saints based too closely on photographs.

Challenge 1: Breaking Free of Source Constraints

The first challenge that an artist must overcome in these circumstances is a difficulty common to historical art in general. When faced with the need to incorporate the recognizable likeness of a past figure into a scene, artists can experience an overriding temptation to take the easy way out by constraining the composition to the viewing angle and lighting of a reference image. This often results in stilted arrangements, especially when the available references are stiff Victorian-era studio portraits or early-modern oil paintings.

Countless examples of artists succumbing to this temptation could be highlighted. To pick an example almost at random, consider John Trumbull’s Surrender of General Burgoyne, which recreates a scene from the 1777 Saratoga campaign of the American Revolution.

John Trumbull, Surrender of General Burgoyne (1821)

Since nearly every participant in the event was a well-known military officer, Trumbull had to capture an array of likenesses based on a limited inventory of portraits painted by other artists. His servile dependence on this source material can be appreciated by comparing specific details with their respective references.

Even without digging up each such comparison, however, the viewer can get a sense of Trumbull’s compositional process by noting how many figures in the scene are shown in perfect three-quarter view, a staple of eighteenth-century portraiture. That this reflects the uniform formality of the source material can be readily inferred, especially since it means that only a few officers seem to be paying attention to the main action. The complete lack of natural interaction between members of the assembled crowd, and between the crowd and the event they are supposed to be witnessing, leaves the viewer with a disjointed and artificial impression.

This impression is particularly jarring when the scene involves intense action. Observe, for example, the American Civil War colonel in this painting by a contemporary artist and compare to the reference photograph here. Note how the incongruity between the formal portrait and the dynamic setting into which it is incorporated significantly detracts from the authenticity of the overall effect.

Finally, for a side-by-side illustration of failure and success in this facet of historical art, consider first Thomas Nast’s depiction of the surrender at Appomattox.

Thomas Nast, Peace in Union (1895)

As with Trumbull’s painting, most of the figures are shown in the three-quarter view of their studio portraits. To compensate, Nast often has them casting creepy sidelong glances at the center of interest, toward which their faces are, at best, only partially directed.

By contrast, here is the same scene in the masterful hands of twentieth-century illustrator Tom Lovell. Even though the respective likenesses have been captured with equal clarity, they have been freed from the constraints imposed by the viewing angle of the sources. Unlike in Nast’s awkward composition, the figures appear to be participating in or observing the action in a natural manner. Freed from dependence on the studio setting, the differing personalities—from Lee’s refined dignity to Grant’s scrappy informality—can emerge in the varied postures and expressions.

As noted above, many existing depictions of the Martins fall prey to the pitfall exemplified by Trumbull and Nast. Successful integration of historical likenesses such as that demonstrated by Lovell, by contrast, requires the artist to undertake the arduous task of reconstructing—at least mentally—the three-dimensional structure of the subject’s face, based often on one or a few two-dimensional references. In the case of our Louis and Zélie, much of the preparatory work was spent in this pursuit, in order that the final composition might be liberated from the constraints of the viewing angles, studio lighting, and formal facial expressions of the photographs.

Pencil sketches, from various angles, exploring Louis’ and Zélie’s facial structures.

This process freed us from having to build the composition around the photographs and gave us full flexibility to design an arrangement suited to the purpose of the commission. We were assisted in this endeavor by several written descriptions of Louis’ and Zélie’s respective appearances that have come down to us, giving details (such as eye and hair color) not readily determined from black-and-white photos.

Challenge 2: Moving Beyond Earthly Likeness

The inherent challenge of painting a scene involving recognizable historical figures is compounded when those figures are being depicted as saints. As Anthony Visco has explained, the photographer’s job is to reveal the saint’s physical attributes in the space-time universe, while the sacred artist’s job is to portray the saint as transfigured in eternity. The distinction, especially within the canon of Western art, is subtle and sometimes difficult to describe. But it is real and critically important.

Achieving this goal requires judicious idealization and abstraction, without undermining the compelling illusionism that is the hallmark of the Western Christian tradition or impairing legibility for viewers familiar with the physical likeness of the saint. That this aim is often lost on contemporary artists, and found difficult by those who try, can be seen by running search-engine image queries for “paintings” of figures like Mother Teresa, John Paul II, Padre Pio, Gianna Molla, and other popular twentieth-century saints.

For a rare contrasting example of a living artist who achieved this balance well, see Leonard Porter and his masterful painting of St. Thérèse of Lisieux. Although based closely on the extant photographs of the saint, and eminently recognizable as a portrait, there is a subtle serenity of expression, perfection of complexion, and radiance of visage that defies easy description but which lifts the subject out of the earthly plane and into a heavenly dimension.

Symmetry

One technique for achieving this effect is to nudge a subject’s features towards greater symmetry. Real human faces are typically close but not quite symmetric. Except in unusual circumstances, where someone is recognized by a particularly deformed or maimed visage, these asymmetries can be corrected without compromising the legibility of the likeness.

Some examples of paintings of saints that employ perfection of facial symmetry to impart the appropriate idealization to the sacred subject include the following.

Raphael, Small Cowper Madonna (ca. 1505)

Guido Reni, St. Sebastian (ca. 1615)

William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Madonna of the Roses (1903)

As I studied the photographs of Louis and Zélie, I noted subtle asymmetries in the lay of Louis’ eyelids and the tip of Zélie’s nose. As I worked on reconstructing the full structure of their faces, I abstracted from these bilateral differences in order to give a sense of glorified perfection not present in the photographs.

Radiance

In the Book of Exodus, after Moses conversed face-to-face with God, his face was so radiant that he had to wear a veil (34:29-35).

Michael Burghers, Moses Veiled (1695)

Accordingly, imparting to a subject a certain brightness of visage can be another subtle but effective way of implying the beatific vision enjoyed by the saint in eternity.

When I think of examples of this effect from Art History, my mind is drawn to Jacob Jordaens’ monumental depiction of Christ blessing the children.

Jacob Jordaens, Suffer the Little Children to Come unto Me (1616)

Although she is not canonized, the anonymous woman in the center of the canvas gazes at Christ and absorbs his teaching—and thus, like the saints in glory, is encountering the Divine.

This encounter is portrayed visually by the radiant expression on her face—a slight smile of transcendent joy, cheeks that almost seem to glow with an inner warmth, and eyes staring with transfixed attention, heedless of the surrounding chaos of whining babies, harried mothers, and grumbling disciples. Note in particular how the circular brim and radial ribbons on the bonnet framing her face act like a halo to heighten the effect.

In composing Louis and Zélie, I tried to capture a similar expression on the faces of the saints.

Of course, the radiance of holiness is also conveyed, to a greater degree of symbolic abstraction, by the presence of halos.

Signs and Symbols

A final method of moving beyond the particularity and literalism of the photographic source material is to introduce signs that integrate the subject into the larger system of Christian symbolism.

In Western Christian painting, especially in the Baroque tradition, lighting schemes are often a primary vehicle of metaphorical meaning. In such artwork, figures emerge from symbolic darkness to be illumined by the light of Divine inspiration or an interior experience of the Holy Spirit.

Mattia Preti, St. Veronica with the Veil (ca. 1653)

Guido Reni, St. Cecilia (1606)

Jusepe de Ribera, Penitent Peter (ca. 1630)

In crafting Louis and Zélie, we certainly relied on this time-honored motif, with the spouses turning to face a symbolic light source in order to emphasize their mutual orientation toward the spiritual goods of their earthly marriage.

In previous times no one knew what the average saint looked like after his or her death, so sacred art developed a canon of symbolic attributes associated with different saints in order to enhance legibility for those who could not read a written title or label. Since Louis and Zélie were only recently canonized, a consistent set of such attributes has yet to be developed for them. The patron who commissioned the present painting, however, suggested including a rose, the readily recognizable symbol of the couple’s most famous daughter, St. Thérèse of Lisieux.

Accordingly, we developed a damask rose motif for the Victorian-style wallpaper pattern and also incorporated the seal of the Carmelite order, to which Thérèse and three of her sisters committed their lives.

A draft of the stylized rose pattern we developed for the wallpaper

The Carmelites’ coat-of-arms

These visual cues connect the painting’s subjects to the basis for their veneration by reminding viewers of how the true sanctity of their seemingly ordinary life of unassuming piety was revealed in the extraordinary holiness of their children.

Bringing It All Together

With the basic elements of the composition in place and endorsed by the patron, we commenced the final oil painting. Our progress day by day, from the initial blocking in of color to the final varnish, can be followed in the time-lapse video.

Compared to the composition process, the execution phase was relatively straightforward, though achieving the print-like uniformity of the complex wallpaper pattern in a way that was legible but not distracting was a challenge unique to this commission. We also had to be careful in managing the edges, with those in the focal areas (such as the light-side border of Louis’ forehead) being very sharp and others (such as the dark-side edge of the clothing around the waist) being nearly lost.

The resulting portrait of Louis and Zélie combines recognizable faces and period clothing with idealized features, metaphorical lighting, and symbolic attributes. In so doing, it seeks to achieve the delicate balance of capturing the saints’ physical likenesses and historical rootedness while at the same time moving beyond literal representation of an earthly scene to stress a transcendent, spiritual reality present in how they lived out their married vocation.

Pope St. John Paul II once said, “As the family goes, so goes the nation, and so goes the whole world in which we live.” We hope that our painting will help to inspire, through the example and intercession of Sts. Louis and Zélie Martin, a renewed respect for the vocation of marriage and a renewed commitment among spouses to marital love and fidelity.

Further Reading

Visco, Anthony. “In the Image and Likeness: The Inadequacy of Photorealism.” Sacred Architecture 27 (Spring 2015): 20-23. <Link>