Anatomy of a Painting I: Francesco Solimena’s Assumption

Introduction

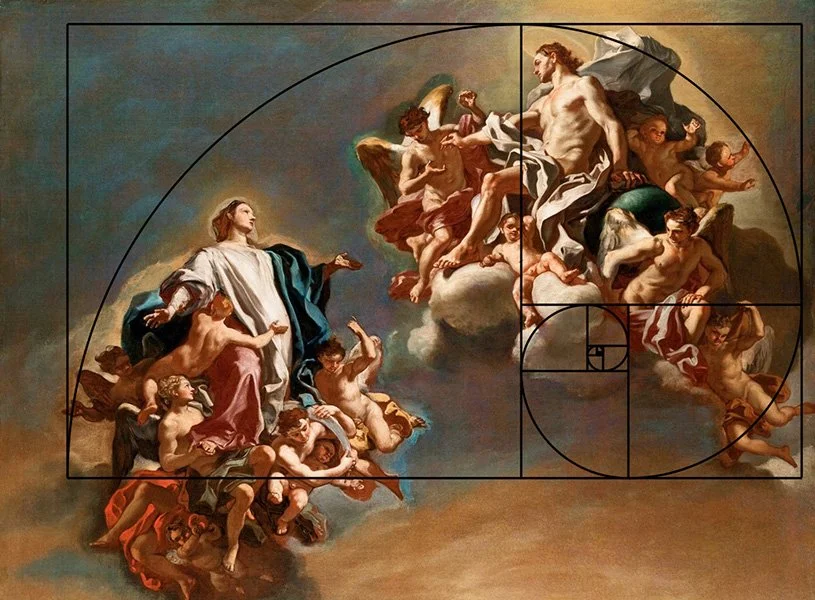

One of my favorite religious paintings of the Baroque era is Francesco Solimena’s Assumption (ca. 1730). The great Italian master completed several canvases with this theme earlier in his career, and in general these are better known today. But I have an affinity for this one, and I think the reasons provide insight into the ingredients of effective sacred art that still resonate today.

In this first of our Anatomy of a Painting series, we’ll analyze the details of Solimena’s composition in order to understand the basis for his success.

Historical Background

One of the most influential painters of his generation, Francesco Solimena moved to Naples in 1674, while still in his teens, and dominated the Neapolitan art scene for decades until his death in 1747 at the age of 89. He trained a number of the most talented artists of the eighteenth century (including two of my favorite sacred artists of all time, Francesco de Mura and Corrado Giaquinto). His style, with its penchant for theatrical compositions, sumptuous models, dramatic lighting, and dense tenebrism, was solidly Baroque, although his work during the first two decades of the 1700s was influenced by the emerging Classicism of Paolo de Matteis and others.

Solimena’s subject matter over the course of his long career encompassed Christian themes as well as portraiture, allegories, and scenes from Classical mythology. As stated above, he completed several canvases portraying the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin, some of which are more familiar than the version under consideration here.

For example, his most famous rendition was executed for the Church of the Annunciation in Marcianise in the late 1690s. With its theater-like setting and rapid transitions between warm brown shadows and saturated highlights, it epitomizes Solimena’s vigorously Baroque background and training.

Marcianise Assumption (1696-97)

Naples Assumption (1708)

Capua Assumption (ca. 1725)

By the time of his 1708 painting for the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine Maggiore in Naples, however, we see a greater simplicity in composition, more structural formality, and Classicizing influences in the portrayal of the figures.

Later in life, Solimena returned to an unapologetically Baroque, even “neo-Pretian” approach, as can be seen in the ca. 1725 opus for the Cathedral of Capua (although remnants of his forays into neo-Classicism are evident in the frontal symmetry of the main figure and the overall monumental layout).

Compositional Analysis

The often overlooked (and certainly underappreciated) version of the Assumption considered here, usually dated to ca. 1730 when Solimena was in his seventies, is probably his final surviving treatment of the subject matter. In it, we see the mature efflorescence of the old master’s artistic voice. The minimal architectural props of previous renditions have been dispensed with entirely to reveal an aerial background of pure abstraction, with nothing to distract from the centrality of the figures.

These include a mobile Blessed Virgin dominating the left-hand register, and, to the right, the stationary destination of her spiritual journey, a risen Christ. The latter, reposing in dominion on the terrestrial sphere, hands what appears to be an eighteenth-century fountain pen to an attendant poised to apply its cap. If you look closely, between the orb and Christ’s left hand you’ll see a corner of the Book of Life, in which he has presumably just finished inscribing his mother’s name.

The painting represents a bold but remarkably effective synthesis of the eighteenth century’s dominant aesthetic strains. For example, the dynamic motion and heavy value contrasts retain the legacy of the still-influential Baroque. At the same time, the superbly proportioned anatomy demonstrates Solimena’s ability to integrate the neo-Classical ideals of the new century, while the figural virtuosity and gentler color palette anticipate the pastel exuberance of the emergent Rococo.

In terms of the categories sketched out in our Sacred Art 101 series, Solimena’s Assumption employs a Baroque Illusionism of style, but, in keeping with the sacred subject, the content of the scene is Supernatural and the mode highly Idealized. For example, the figures exhibit Classical proportions and universalized features, while the undulating drapery displays a certain perfection in the uncluttered folds, coupled with an uncanny weightlessness that permits it to break free from the constraints of Fallen reality.

The primary compositional structure of the painting is chiastic…

…though a keen observer may discern a Fibonacci spiral lurking.

The mass is balanced between left/right and top/bottom, but the confident use of negative space means that one arm of the chiasm (red in the diagram) serves to divide the canvas into the fully glorified vs. the becoming glorified…

…while the blue arm defines the axis of narrative flow.

The symmetry and equilibrium of the chiastic arrangement conveys a monumental stability to the composition that complements its dynamic motion.

Speaking of motion, Solimena has chosen a horizontal rather than a vertical orientation for this version—a creative departure from iconographic tradition for a subject inherently defined by upward movement. The primarily rightward direction of the scene’s physical velocity and logical progression synergizes with the way we read and thus flows more naturally and with greater force than if the composition proceeded right to left. There is still an upward component to the motion vector, however, sufficient to convey the metaphorical message of heavenly glorification.

Having eliminated any hint of an architectural setting, and even an empty tomb surrounded by astonished Apostles, Solimena is free to focus the viewer’s attention on the poignant encounter between Christ and his mother—at once profoundly affecting and yet characterized by an appropriately dispassionate and otherworldly peace. In the hands of a lesser artist, the frenetic activity of the angels would be distracting, but the interlocking gaze of the two protagonists keeps the viewer’s visual path focused, ping-ponging back and forth between the central figures in a recapitulation of their mutual love.

This masterful compositional device imparts to the whole a surprising dignity and noble simplicity that belies the multi-figural complexity of its component parts.

The painting, of course, is not without its shortcomings. The (primarily light-colored) outlining of the main blocks of figures, delineated in purple below, helps to set them off from the background and thereby improves legibility. In the case of the left-hand register, the trailing effect even contributes to the sense of motion. But the manner in which this “outer glow” clings to the contour of the foreground elements ruins the sense of depth and unnecessarily flattens the overall effect.

Second, the artist has too obviously relied upon a single model for two different figures.

The position of each in the lower right of his respective mass lends a sense of symmetry, but the parallel is far too literal. Such a careless shortcut is surprisingly amateurish for a work of this caliber and maturity.

Finally, while most of the figures display admirable Classical proportioning, the wingless angel beneath Mary’s right arm has an abnormally small head—or at least anatomy that is overly adult-like for an individual scarcely larger than the cherubs.

This strange distortion adds a surely unintentional note of discord to the otherwise harmonious composition.

Conclusion

Despite these defects, Solimena’s Assumption remains a tour de force of effective visual representation in the Western Christian tradition. The powerful narrative flow and evocative portrayal of supernatural ideals, all mediated by a striking but accessible Illusionism, serve as a template for achieving the elusive balance between legibility and abstraction that lies at the heart of proper sacred art. It is time for this little known and rarely seen work to take its rightful place among the artist’s finest and most respected masterpieces.

Further Reading

Blumenthal, Arthur R. In the Light of Naples: The Art of Francesco de Mura. Winter Park, FL: Cornell Fine Arts Museum, Rollins College, 2016.

Bologna, Ferdinando. Francesco Solimena. Naples: Arte Tipgrafica, 1958.